Design overview

Let's discuss some architectural and design topics about Centrifugo.

Idiomatic usage

Centrifugo is a standalone server that abstracts away the complexity of working with many persistent connections and efficiently broadcasting messages from the application backend. The fact that Centrifugo acts as a separate service dictates some idiomatic patterns for how to integrate with Centrifugo for real-time message delivery.

Usually, you want to deliver content created by a user in your app to other users in real time. Each user may have several real-time connections with Centrifugo. For example, a user opened several browser tabs, with each tab creating a separate connection. Or a user has two mobile devices and created a separate connection to your app from each of them. We call a connection a client in Centrifugo. Thus, the words connection and client are synonyms for us.

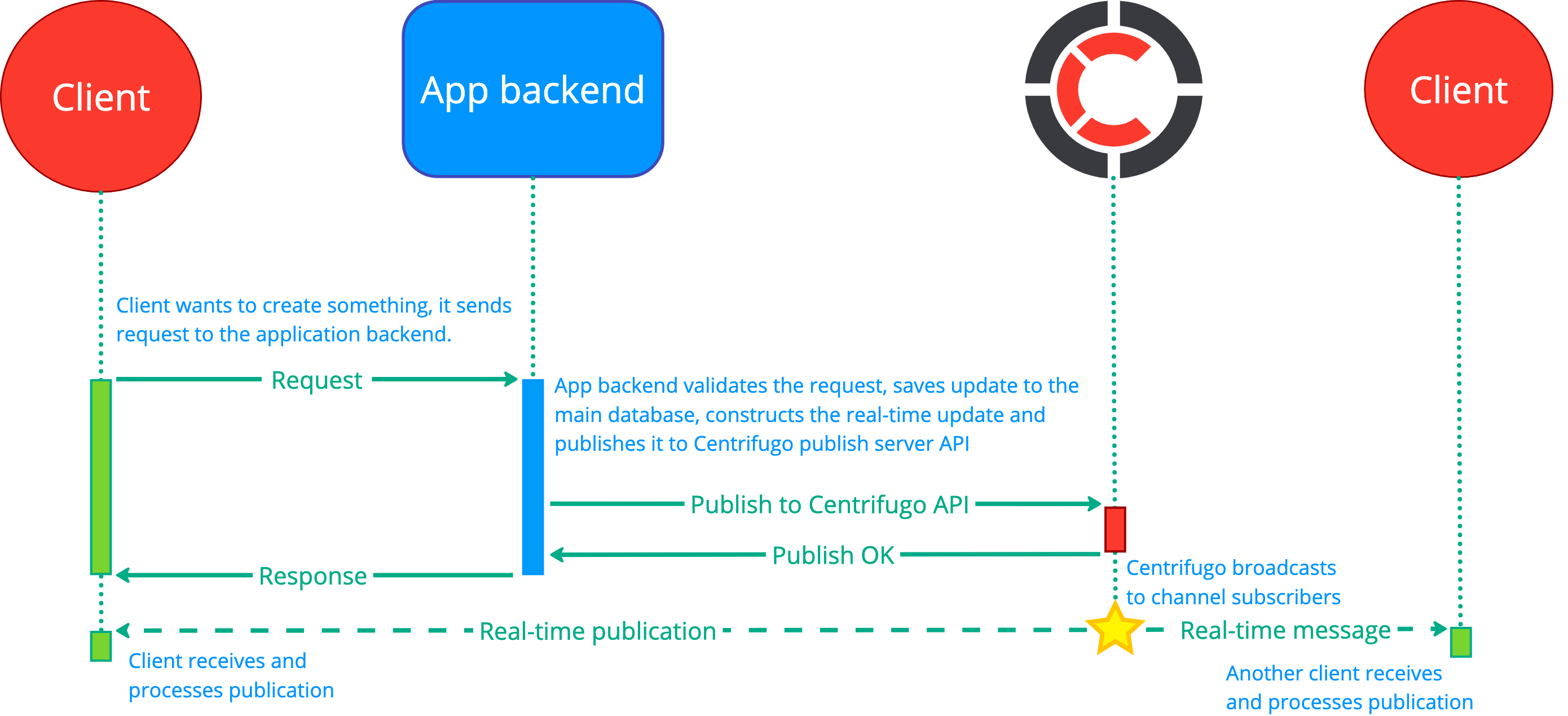

All requests from users that generate new data should first go to the application backend – i.e., calling the app backend API from the client side. The backend can validate the message, process it, save it into a database for long-term persistence – and then publish an event to a channel using Centrifugo server API. This event is then efficiently broadcast by Centrifugo to all active channel subscribers.

The following diagram shows the process (assuming the client that generates new content is also a channel subscriber and thus also receives the real-time message):

This is usually a natural workflow for applications since this is how applications traditionally work (without real-time features) and Centrifugo is fully decoupled from the application in this case.

Centrifugo serves the role of a real-time transport layer in this case, and you may design the app with graceful degradation in mind – so that removing Centrifugo won't be a fatal problem for the application – it will continue working, just without the real-time features.

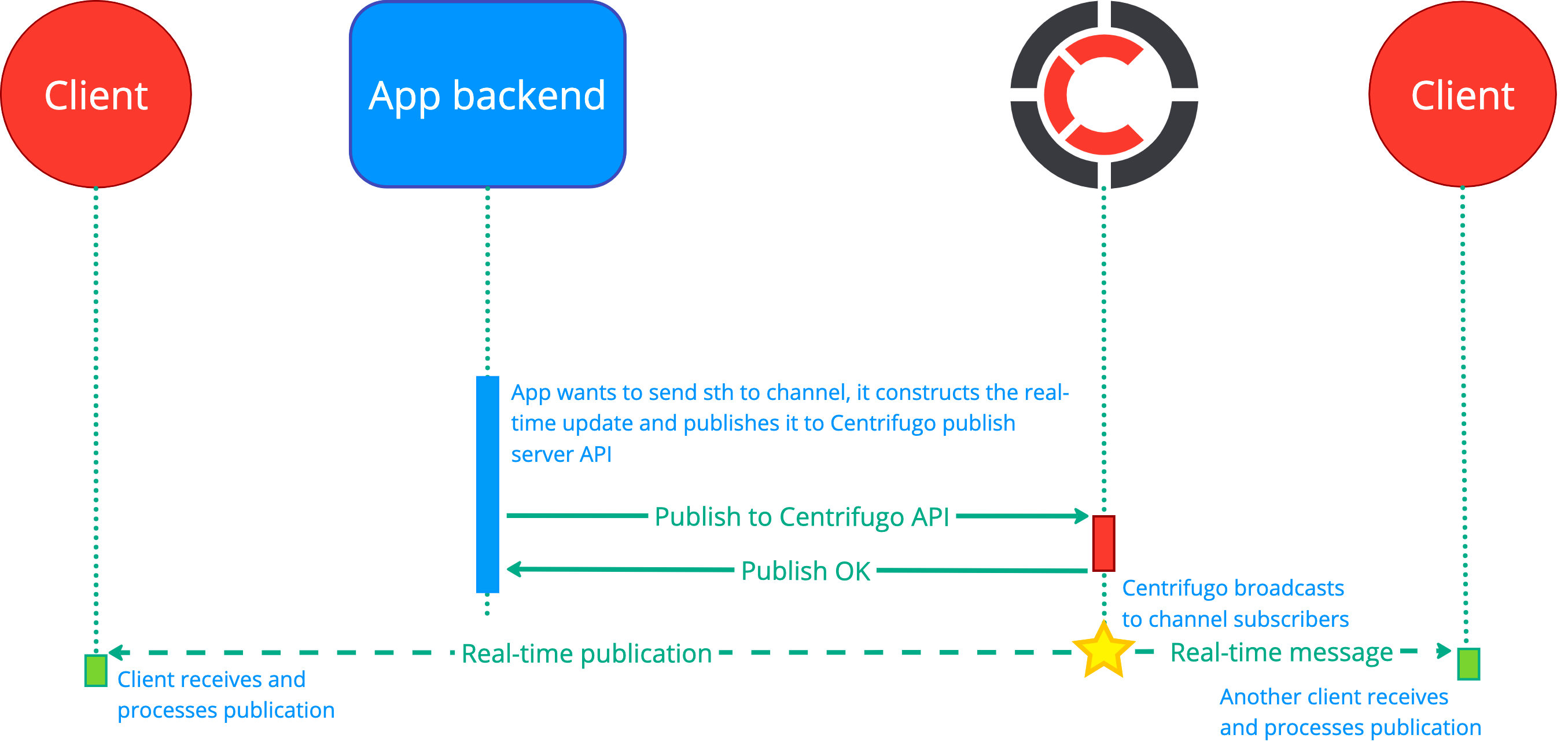

If the original source of events is your app backend (without any user involvement) – then the above diagram simplifies to:

So the backend publishes data to channels and if there are active subscribers – events are delivered. If there are no active subscribers then events are dropped by Centrifugo (or, in case of using history features in channels, events may be temporarily kept in the Centrifugo history stream).

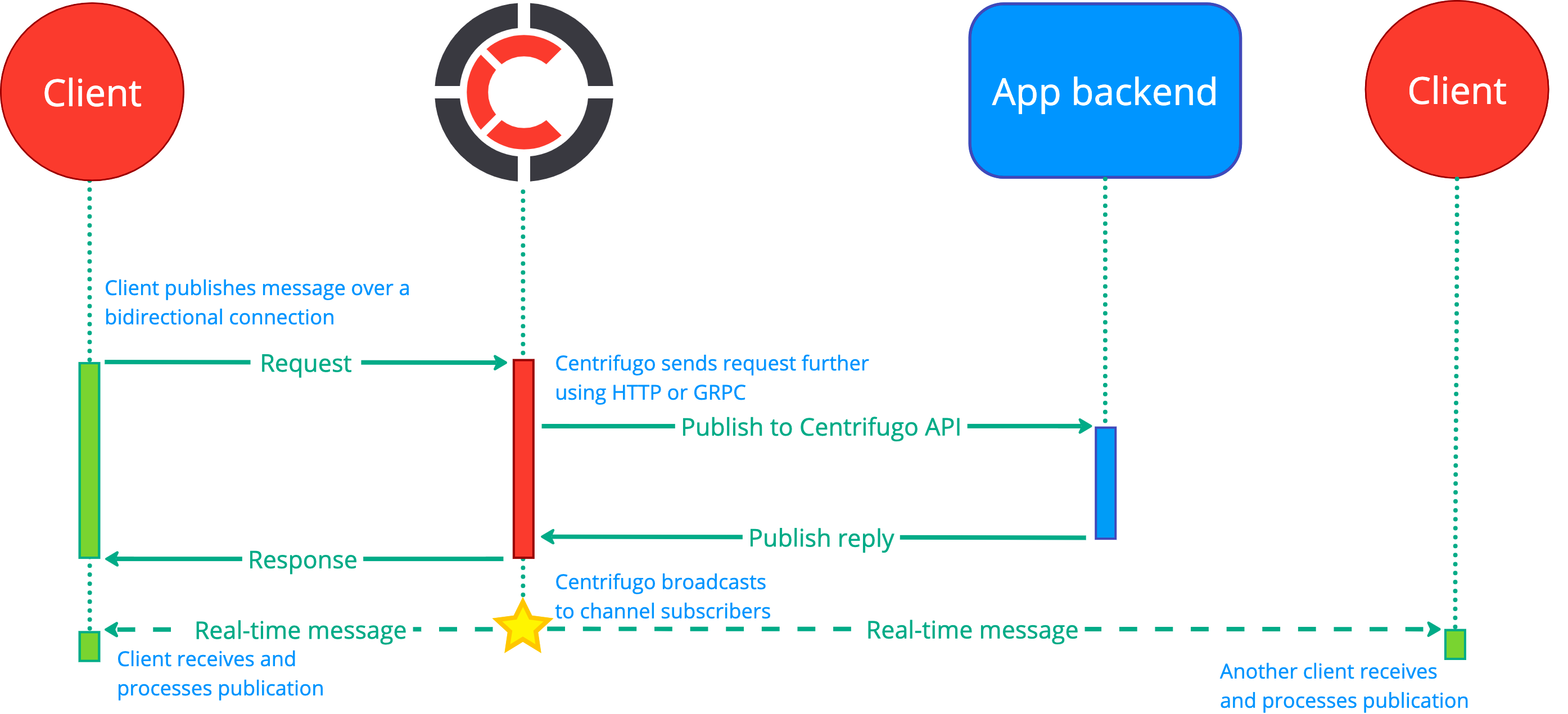

It's also possible to utilize Centrifugo's bidirectional connection for sending requests to the backend. To achieve this, Centrifugo provides event proxy features. It's possible to send RPC (with a custom request-response) requests from the client to Centrifugo and the request will then be proxied to the application backend (see RPC proxy). Moreover, the proxy provides a way to utilize the bidirectional connection for publishing into channels (using publish proxy). But again – in most real scenarios, your backend must validate the publication attempt, so the scheme will look like this:

Message history considerations

Idiomatic Centrifugo usage requires having the main application database from which the initial and actual state can be loaded at any point in time.

While Centrifugo has channel history, it has been mostly designed to be a hot cache to reduce the load on the main application database when all users reconnect at once (in case of a load balancer configuration reload, Centrifugo restart, temporary network problems, etc.). This allows for a radical reduction in the load on the application's main database during a reconnect storm. Since such disconnects are usually pretty short in time, having a reasonably small number of messages cached in history is sufficient.

The addition of the history iteration API shifts possible use cases a bit. Manually calling history chunk by chunk allows for keeping a larger number of publications per channel.

Depending on the Engine used and the configuration of the underlying storage, history stream persistence characteristics can vary. For example, with the Memory Engine, history will be lost upon Centrifugo restart. With Redis engine, history will survive Centrifugo restarts, but depending on the storage configuration, it can be lost upon storage restart – so you should take into account storage configuration and persistence properties as well. For example, consider enabling Redis AOF with fsync for maximum durability, or configure replication for high availability, use Redis Cluster.

When using history with automatic recovery, Centrifugo provides clients with a flag to distinguish whether the missed messages were all successfully restored from Centrifugo history upon recovery or not. If not – the client may restore the state from the main application database. Centrifugo message history can be used as a complementary way to restore messages and thus reduce the load on the main application database most of the time.

Message delivery model

By default, the message delivery model of Centrifugo is 'at most once'. With history and the positioning/recovery features enabled, it's possible to achieve 'at least once' guarantee within the history retention time and size. After an abnormal disconnect, clients have an option to recover missed messages from the publication channel stream history that Centrifugo maintains.

Without the positioning or recovery features enabled, a message sent to Centrifugo could theoretically be lost while moving towards clients. Centrifugo makes its best effort only to prevent message loss on the way to online clients, but the application should tolerate the loss.

As noted, Centrifugo has a feature called message recovery to automatically recover messages missed due to short network disconnections. It also compensates for the 'at most once' delivery of a Redis broker PUB/SUB system by using additional publication offset checks and periodic offset synchronization. So publication loss missed in the PUB/SUB layer will be detected eventually, and the client may catch up on the state by loading it from history.

Message order guarantees

Centrifugo server publish API guarantees message order within a channel only when messages are published sequentially or within a single request. If messages are published in parallel, ordering is not guaranteed due to concurrent processing.

In detail:

- If you publish message 1, wait for the request to complete, and then publish message 2 to the same channel, Centrifugo ensures that subscribers receive the messages in the correct order: message 1, then message 2.

- If message 1 and message 2 are published concurrently to the same channel, the delivery order is not guaranteed. Subscribers may receive them as message 1 then message 2, or vice versa. However, all subscribers will receive the messages in the same order.

The same is applied for publishing over real-time client protocol publish method.

When using asynchronous consumers, ordering also depends on the consumer implementation. For example, Kafka can preserve order within partitions, while other systems may not guarantee any ordering. Refer to the particular consumer description.

Graceful degradation

It is recommended to design an application in a way that users don't even notice when Centrifugo does not work. Use graceful degradation. For example, if a user posts a new comment over AJAX to your application backend - you should not rely solely on Centrifugo to receive a new comment from a channel and display it. You should return new comment data in the AJAX call response and render it. This way, the user that posts a comment will think that everything works just fine. Be careful not to draw comments twice in this case because you may also receive the same data from a channel - think about idempotent identifiers for your entities.

Online presence considerations

Online presence in a channel is designed to be eventually consistent. It will return the correct state most of the time. But when using Redis engine, due to network failures and the unexpected shutdown of a Centrifugo node, there are chances that clients can be present in a presence for up to one minute more (until the presence entry expires).

Also, channel presence does not scale well for channels with a lot of active subscribers. This is due to the fact that presence returns the entire snapshot of all clients in a channel – as soon as the number of active subscribers grows, the response size becomes larger. In some cases, the presence_stats API call can be sufficient to avoid receiving the entire presence state.

Scalability considerations

Centrifugo can scale horizontally with built-in Redis engine or with the Nats broker. See engines.

All supported brokers are fast – they can handle hundreds of thousands of requests per second. This should be enough for most applications.

But if you approach broker resource limits (CPU or memory), then it's possible:

- Use Centrifugo's consistent sharding support to balance queries between different Redis broker instances.

- Use Redis Cluster (it's also possible to consistently shard data between different Redis Clusters).

- Nats broker should scale well itself in a cluster setup.

All brokers can be set up in a highly available way so there won't be a single point of failure.

All Centrifugo data (history, online presence) is designed to be ephemeral and have an expiration time. Due to this fact, and the fact that Centrifugo provides hooks for the application to understand history loss, makes the process of resharding mostly automatic. As soon as you need to add an additional broker shard (when using client-side sharding), you can just add it to the configuration and restart Centrifugo. Since data is sharded consistently, part of the data will stay on the same broker nodes. Applications should handle cases where channel data moved to another shard and restore the state from the main application database when needed (i.e., when the recovered flag provided by the SDK is false).